Asaf Zeynalli: “Fantasy in Mugham Style” Contest

May 14, 2020

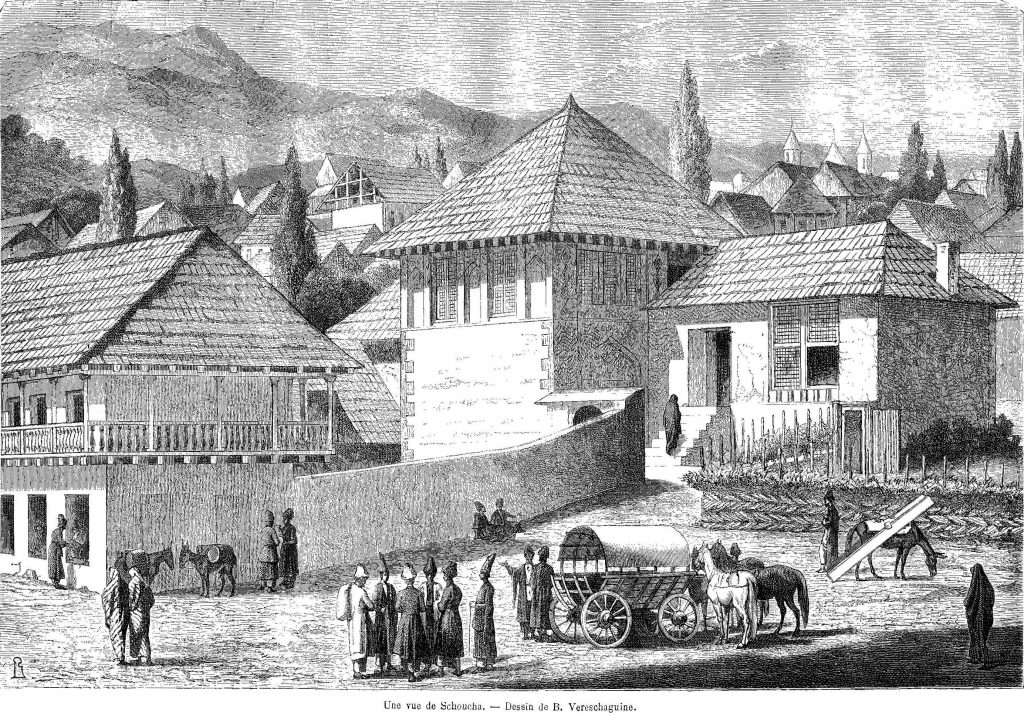

Gara Garayev: Sailing in Stormy Seas

February 6, 2021Shusha: The Music Capital of Azerbaijan is courtesy of Dr. Zemfira Safarova, a well-known academician, and musicologist from Azerbaijan. The article is dedicated to the fascinating history of Shusha’s music and musicians, the cultural capital of Azerbaijan located in the heart of the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan. Initially published in the Russian language in 2009, the article’s modified English translation is provided to accommodate our readers. Definition of terms concerning Azerbaijani music and folk instruments, as well as photo illustrations, were added to ensure effortless reading. We hope you will take some time to explore Karabakh’s musical art’s rich history and get to know its distinguished representatives.

Dr. Jamila Javadova-Spitzberg, Founder and Executive Director, AAMF

Shusha: A Music Capital of Azerbaijan by Dr. Zemfira Safarova

There are a few cities in the world where every single stone, every street, in short, the whole ambiance is saturated with music. Among them, Vienna in Austria, Naples in Italy, and Shusha in Azerbaijan, to name a few. Located in Western Azerbaijan, Shusha is considered to be a center of Azerbaijani culture. As the outstanding Azerbaijani poet Samad Vurghun said, “almost all famous singers and musicians of Azerbaijan are natives of Shusha. It’s no coincidence that Shusha is called the cradle of music and poetry.” Many have rightly acknowledged this city as the “Conservatory of the Caucasus.” In 1938, in his book “Uzeyir Hajibeyov and Azerbaijani Music,” the well-known Russian researcher of oriental music V. Vinogradov, wrote the following: “There is an abundance of music in Shusha; you can hear folk songs, dances, singers and instrumentalists more than in any other regions of Azerbaijan.” Shusha has been a reputed center since ancient times and famous throughout the South Caucasus as an inexhaustible source for musical talents. Musicians of this town made the history of Azerbaijani music and presented it not only in their homeland but also in other countries of the East.”. (Vinogradov V.S. “Uzeir Hajibeyov and Azerbaijani music.” Moscow, 1938, p. 9).

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the magnificent Shusha school of mugham was formed, consisting of several brunches led by prominent mugham performers, khanendes. This School became famous not only in the South Caucasus but throughout the Middle East. In the eighteenth century, the poet Molla Panah Vagif lived and worked in Shusha; his poetry had a significant impact on the development of Azerbaijani literature and music. Molla Panah Vagif’s poems formed the basis of many folk songs. Vagif’s poetry also attracted mugham performers.

On the one hand, mugham’s performance is strictly characterized by the use of patterns of the modal system intonations, dramaturgical lines, and the structure. On the other hand, it calls for an interplay between canonic principles and performers’ artistic inventiveness. The emergence of Shusha mugham performers’ School is closely associated with this eternally “singing city.” They played a huge role in enriching and developing the Azerbaijani mugham with new and challenging techniques, bright and expressive colors, innovative approaches to dastgah‘s structure. (a mugham suite; a complete composition comprising multiple sections).

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, musical societies or forums called Majlis were created in many Azerbaijan cities. These traditional oriental forums of poets, musicians, scientists, artists, and patrons of the art played an essential role in people’s lives. Majlis gatherings were centered around debates and discussions on artistry and performance, the central theme of mugham art. The founder of the popular Majlisi-Uns (Society of Friends) of Shusha was a talented poetess and artist Khurshidbanu Natavan. Another exciting piece of information has been preserved about the Majlis created in Shusha by the connoisseur of classical oriental music, Kharrat Guli (1823-1883), a carpenter. At these gatherings, along with religious chants accompanying ritual actions in the month of Muharram (second holiest month, after Ramaḍān in the Islamic calendar), singers also learned the art of mugham singing. After completing the funeral performances, for which they had been preparing for several months, the khanendes performed the same mughams in a secular setting – at weddings and other festivities. The Kharrat Guli Vocal School’s prominent representatives were singers Haji Husu, Mashadi Isi, Abdulbagi Zulalov, Deli Ismail, Keshtazly Hashim, Kechachioghlu Muhammad, and Jabbar Garyaghdioghlu.

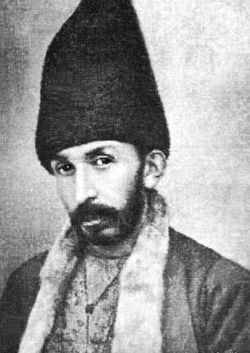

In the 1880s, in Shusha, the Majlis-i-Faramushan (Society of the Forgotten) and the Society of Musicians were established. They were led by Mir Mohsun Navvab Karabaghi Shushinskiy (1833-1918), a progressive figure: scientist, musicologist, poet, and calligrapher in Azerbaijan. Navvab was born, lived, worked, and died in Shusha. A man of in-depth knowledge, he significantly contributed to Azerbaijani science, literature, and art. The versatile scientific activity of Navvab was reflected in more than twenty of his works. He was an expert in astronomy and chemistry, well-versed in ancient philosophy and ethics. Navvab wrote poetry and provided illustrations to the anthology of poems of the poets of Karabagh. He has also collected and took part in the painting of the Shusha’s famous Govhar-Agha mosque.

Navvab’s work done in the field of music and performance is of particular interest. In the Society of Musicians of the 1880s, singing styles, poems accompanying classical mughams, and many other artistic problems were discussed. The Society included famous musicians of its time, singers and instrumentalists Haji Husu, Mashadi Jamil Amirov, Islam Abdullaev, and Seyid Shushinskiy. Many musicians received their initial education at this Society. Some of the creative ideas discussed during the Society’s gatherings were reflected and further developed in Navvab’s treatise Vizuhil-Argam (Explanation of the Ciphers), written in 1884. It is fascinating that this treatise was drafted when in the Middle East, the tradition of musical treatises had practically exhausted itself; hardly any new works were created, and medieval ones were copied. Yet, in Shusha, this tradition continued, and Navvab revived it.

In his treatise, Navvab examines features of oriental musicology in relation to Azerbaijani music. It appears as a novel practical guide to studying the mugham genre’s properties and rules. According to the tradition of medieval treatises, problems pertaining to music’s origins, aesthetics, acoustics, and a correlation between text and music were examined. Navvab also addresses the link between music and medicine and talks about music’s healing properties. In that, Navvab undoubtedly emerges as a successor of Avicenna’s teachings. Like philosophers of The Brethren of Purity Society of the tenth and eleventh centuries who explored the individual perception of music by various people, Navvab also dwells on this characteristic feature by providing parallels with corresponding contemporary mughams. He attributes the origins of mugham to organic processes. Thus, “the mother of all mughams,” Rast, reminds the gentle coolness of the spring breeze, while mugham Chahargah resembles a thunderstorm. For Navvab, a correlation between music and poetic text is essential. It’s an integral part of mugham performance; thus, a choice of proper poetic verses become a prerequisite for him.

A great deal of interest represents the pages of the treatise devoted to the rules of music perception. Alluding to Aristotle, Navvab indicates a series of considerations regarding the practices of performance and perception of music. He attaches great importance to the social setting of the performers and the audience, to the appearance of khanandes, and the sound environment. It testifies to the existence of a high level of musical and performing culture of Shusha in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the treatise, Navvab defines the dastgah term, discloses parts of the Rast, Mahur, Shahnaz, Rashavi, Chahargah, Nava mugham sets, and talks about the importance of the order in arranging parts of the dastgah. The beginning and the end of mugham, ascending and descending lines, sectional transitions, tonality, and various virtuoso singing techniques, including zengule (grace-notes), according to Navvab, are quintessential components of mugham performance practice. Navvab directs readers to a table containing all the standard contemporary dastgahs and their sections. The corresponding figures indicate the number of mughams, shobeh (division), avaz (unmetered vocal section), and gushe (melodic developments that represent the various potential dynamics of a mugham set) contained in the art of mugham.

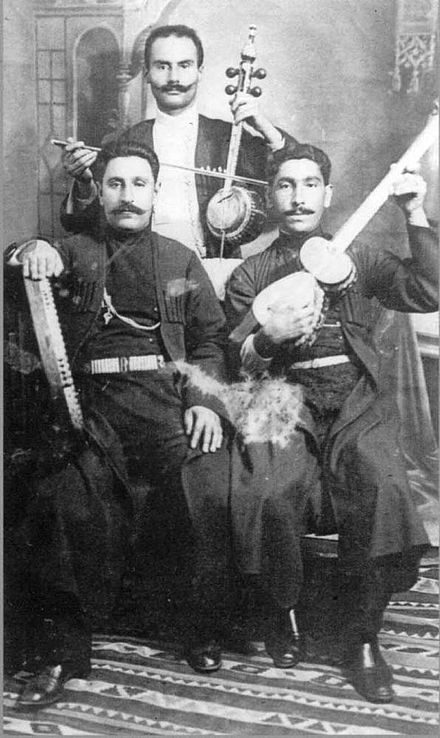

One of the outstanding representatives of Shusha’s vocal art school was Haji Husu (1830-1898), a pupil of Kharrat Guli. His premier performance at a charity evening in front of Shusha residents took place at the Khandemirov Theatre. Haji Husu, accompanied by the famous tar player (a long-necked, plucked lute) Sadykhdzhan (more on him below), brilliantly sang the mugham Chahargah, winning the audience’s hearts. His fame spread quickly. Haji Husu was also an expert on the theory of mugham, was aware of performance practices of this genre in many countries of the Middle East, and the peculiarities of mugham in Azerbaijan. He enhanced the expressiveness and structural properties of several local mughams, creating new versions of them. Thus the mugham Kurdi-Shahnaz. Haji Husu added another section, Shahnaz, to the traditional mugham Kurdi, which gave the form a significant scope, and deepened the emotional and dramatic content. Haji Husu was also the author of the Gatar mugham. He received invitations to festivities throughout Azerbaijan and in many cities of the Near and Middle East. Poetess Natavan favored Haji Husu, who was a frequent guest at her Majlises. Famous musicians, Mashadi Melik Mansurov of Baku, Mahmud Agha of Shamakhy, and many others often had the honor of his presence at their musical evenings. In 1880, the Shah of Iran, Nasreddin, invited him to Tabriz to perform at his son’s wedding. Haji Husu was accompanied on tar by Sadykhdzhan and on kamancha (bowed string instrument) by Baghdagul Ata. He also sang together with many famous musicians in Iran and received an award from Iran’s Shah. During the last years of his life, after returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca, Haji Husu, under pressure from religious authorities, stopped performing mughams and only chanted azan from the minaret (a tall, slender tower) of the Shusha’s mosque Govhar Agha, calling the faithful for prayer. But even then, his voice attracted numerous listeners not only in Shusha but also in neighboring villages.

The outstanding Shusha tar player Mirza Sadig Asadoghlu (1846-1902), known as Sadykhdzhan, often accompanied the performances of Haji Husu. He won wide popularity and love of people in the entire Caucasus and beyond. Together with Haji Husu at the Shah’s son’s wedding in Tabriz, Mirza Sadig was awarded a gold medal. The pseudonym Sadykhdzhan was a manifestation of the people’s great love for him. Mirza Sadig left behind the legacy of an outstanding musician. He reconstructed and improved the centuries-old plucked tar. Sadykhdzhan improved the instrument by adding four to six sympathetic strings to the original five strings instrument. He also straightened the back of the sound cavity and changed the player’s manner; the tar is now held against the chest rather than rested on the knee. Sadykhdzhan brought the fretboard of the renewed tar up to seventeen, adding extra tones to the instrument. To increase the resonance, Sadykhdzhan added the upper register and introduced the performing style called lal barmag (mute finger). The beloved master of the modern-day instrument, Sadykhdzhan, received the name of the “father of the tar.” He had big hands, long and strong fingers. People were saying that no one could play tar as Sadykhdzhan. But, I want to note that Sadykhdzhan’s excellent school of playing was continued by famous musician performers such as Mashadi Zeynal, Mashadi Jamil Amirov (father of the composer Fikret Amirov), Shirin Akhundov, and the magnificent Gurban Primov, so famous in the twentieth century.

By the end of the nineteenth century, amateur theatrical performances using classical poetry of the East became popular in Shusha. A little scene from Fizuli’s poem Leyli and Majnun and an excerpt from the Ashyg Garib story were among them. In Shusha, in 1987, of particular interest was the staged musical performance of the scene of “Majnun on the grave of Leyli,” directed by the remarkable writer Abdurrahim bey Haghverdiyev. The play was accompanied by mughams, tasnifs (a song inside mugham; can be performed independently outside of mugham too), folk songs performed by a trio of sazandars (a singer-khanende + virtuoso instrumentalist, generally in the form of a trio), and a unison choral group. Staged for local people in Shusha, this live theatrical performance made an indelible impression on the thirteen-year-old Uzeyir Hajibeyli, a choral group singer who would become a founder of the classical compositional school in Azerbaijan. “This picture excited me so deeply that having arrived in Baku, I decided to write an opera,” Hajibeyov wrote years later. Thus, Shusha’s amateur theatrical performance became the forerunner of the first Azerbaijani opera, “Leyli and Majnun.” The plot, its ideas, and most importantly, mugham as the primary musical and dramatic art, received an original embodiment in a new professional genre for Azerbaijani music.

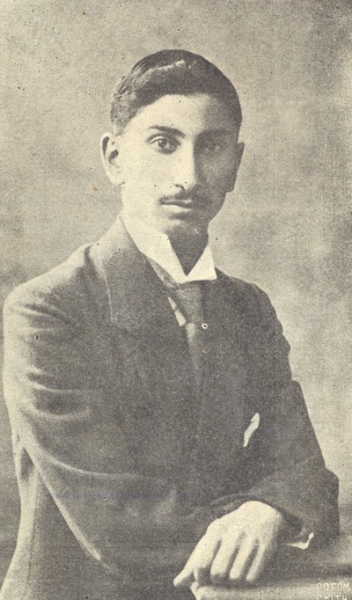

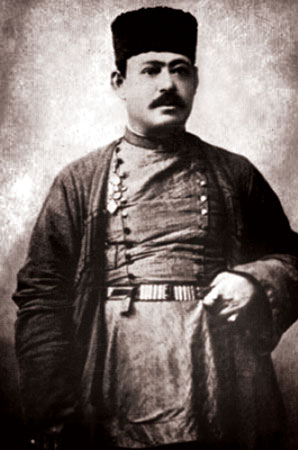

In connection with the scene staged in Shusha by A. Hagverdiyev, special attention should be given to the magnificent performer of Majnun’s role, singer-khanende Jabbar Garyaghdyoghlu (1861 – 1944). He was a multifaceted artist who became widely known both as a khanende and as a composer. His song Baku was well-known in the 1930s and 1940s.

Jabbar was an excellent tenor. Between 1906-1912, his voice was recorded using phonautograph by several joint-stock companies in Kiyev, Moscow, and Warsaw. In the performance of the mughams Mansuriyya, Heyrati, and Kurdi-Shahnaz, Jabbar had no equals. People compared his voice to the great Caruso. Poet Sergei Yesenin, who heard him singing when he was in Azerbaijan, called Garyaghdyoghlu “the prophet of oriental music.” Jabbar Garyaghdyoghlu, an exceptional and virtuoso singer, opened a new page in the history of the Azerbaijani vocal art.

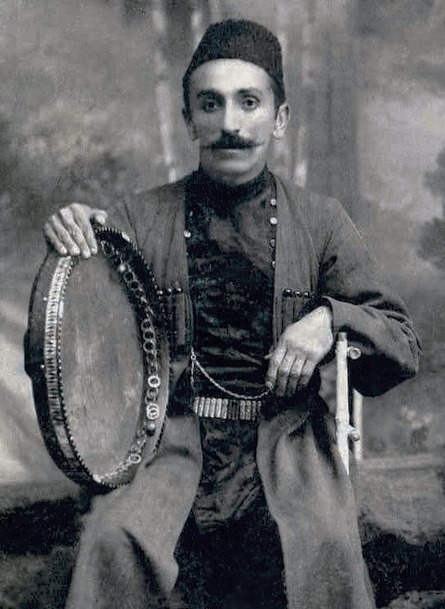

The most prominent representative of the Shusha vocal school, a follower of Garyaghdyoghlu, was Seyid Shushinskiy (1889-1965). Garyaghdyoghlu considered him “the pearl of oriental music.” In 1908, in Shusha, after the first successful performance by Seyid Shushinskiy, Garyaghdyoghlu took the stage, hugged the khanande, and said: “Now I no longer fear death and do not grieve: after me, Seyid remains.” At one of the subsequent performances of Seyid, Jabbar presented him with his daf (shallow round shaped drum used by khanendes). A voice of rare beauty, Seyid Shushinskiy learned the secrets of vocal art, initially from Navvab, with whom he studied for two years, and later from Jabbar Garyaghdyoghlu. He masterfully performed the Chahargah mugham with his unique voice, one of the most challenging mughams for singers. Seyid Shushinskiy’s interpretation of the Chahargah dastgah was unique. He didn’t follow the traditional outline of the Chahargah mugham. Instead of beginning the performance with the conventional Maye section (central/opening), the singer would crescendo into the Mansuriyya, a passionate and intense part of the dastgah, skilfully executing grace notes and only then reducing the intensity and establishing calmness. Even during his final years, when he was well over seventy, Seyid Shushinski sang Mansuriyya with the same brilliance. He was also an excellent performer of the mughams Mahur, Nava, Mani, Arazbary, and Heyraty. Trailblazer Shushinski merged various mughams and created new models, among them Rast-Humayun, Gatar-Bayaty, and Shur-Shahnaz. It was Seyid Shushinskiy who introduced the Dilkesh section into the Rast and Kurdi-Shahnaz dastgahs.

Along with the ghazals (a lyric poem with a fixed number of verses) of the classic poets of Hafiz, Fizuli, and Seyid Azim Shirvani, Seyid Shushinskiy turned to the poetry of his contemporaries, Huseyn Javid and Mirza Alakbar Sabir, when performing mughams and tasnifs. Shushinski was the first Azerbaijani khanende using social and political poems in his singing. He made friends with such progressive figures of his time as Mirza Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, Abdurrahim bey Hagverdiyev, Huseyn Javid, and Huseyn Arablinskiy. Seyid provided financial assistance to publish several issues of his time’s famous satirical magazine, Molla Nasreddin. A great philanthropist, he supported many khanandes and actors.

Another master of mugham, a native of Karabagh, Zulfugar Adigezalov (1898-1963), possessed a beautiful voice and found his way to the listener’s hearts. At the end of the 1920s, Jabbar Garyaghdyoghlu heard him in one of the Shusha Majlises and invited him to Baku. The singer gave concerts at the Philharmonic Hall and performed in mugham operas on the opera house stage. Because of his clear diction, stage artistry, Zulfugar Adigezalov quickly gained popularity as an actor. People affectionately called him “Zulfi.” Just as Jabbar forever glorified himself by performing the mugham Mahur, Seyid – Chahargah, and Islam Abdullaev – Segah, mugham Rast became a crown for Zulfi Adigezalov. He sang it with special skills, inherent only to him, in a unique manner, emphasizing the characteristic features. Adigezalov was an excellent performer of the folk songs Nabi, Kyaklik, and Dedim Bir Buse Ver as well. The tasnif, Men Gedirem Zangilana, sounded especially outstanding. Zulfi Adygozalov’s voice was preserved in the Azerbaijan film studio films – Peasants, Sabuhi, and Baku People.

One of the last leading figures of the Shusha vocal school, Khan Shushinskiy (1901 -1979), Isfandiyar Javanshir by birth, was praised in the poem Azerbaijan by Samed Vurghun. Countless poets glorified Karabagh and Shusha in their poems for centuries. In the twentieth century, numerous verses were devoted to Khan Shushinskiy and his talent. The first teacher of the young Isfandiyar was Islam Abdullayev, who crowned him with the name “Khan Shushinskiy.” Once, at one of the Shusha Majlises, both the famous master and his young, still little-known student, appeared together. Islam asked the house owner to put on a gramophone recording of the Kurdi-Shahnaz mugham sung by famous Tabriz singer-khanende Abul-Hasankhan. Guests were eager to hear young Isfendiyar sing this mugham. His masterful performance in a complicated upper register amazed the listeners, and the teacher proudly named him “Khan,” a title given to rulers and officials in Central Asia. Mugham experts confirmed that Isfendiyar sang like a “real khan.”

According to the singer himself, Jabbar Garyaghdyoghlu and Seyid Shushinskiy played an essential role in boosting his skills. Possessing a strong voice with a wide range and high tessitura, Khan Shushinskiy sang all mughams with great skill, but no one sang Mahur-Hindi like him. Khan flawlessly performed all the versions of the mugham Segah, and with particular brilliance – the Karabagh Shikestesi. He was a skillful daf player and thus very successful in interpreting rhythmic mughams. Khan Shushinskiy was an excellent performer of the song Gara Gyoz (“Black Eyes”) by Uzeyir Hajibeyov. He was the author of many songs, including the very popular Gemerim, Ay Gyozal, Menden Gen Gezme, and Shushanin Daghlary Bashy Dumanly. (“The peaks of Shusha Mountains are Covered with Fog”).

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the high level of musical culture in Karabagh turned this city into the cradle of Azerbaijani classical music. “Shusha supplied the South Caucasus with musicians and singers. It was the blessed homeland of poetry, music, and songs. Shusha served as a conservatory for the entire South Caucasus, supplying it with new songs and new melodies every season and even month” (Caucasian music, Tiflis, 1908, p. 28).

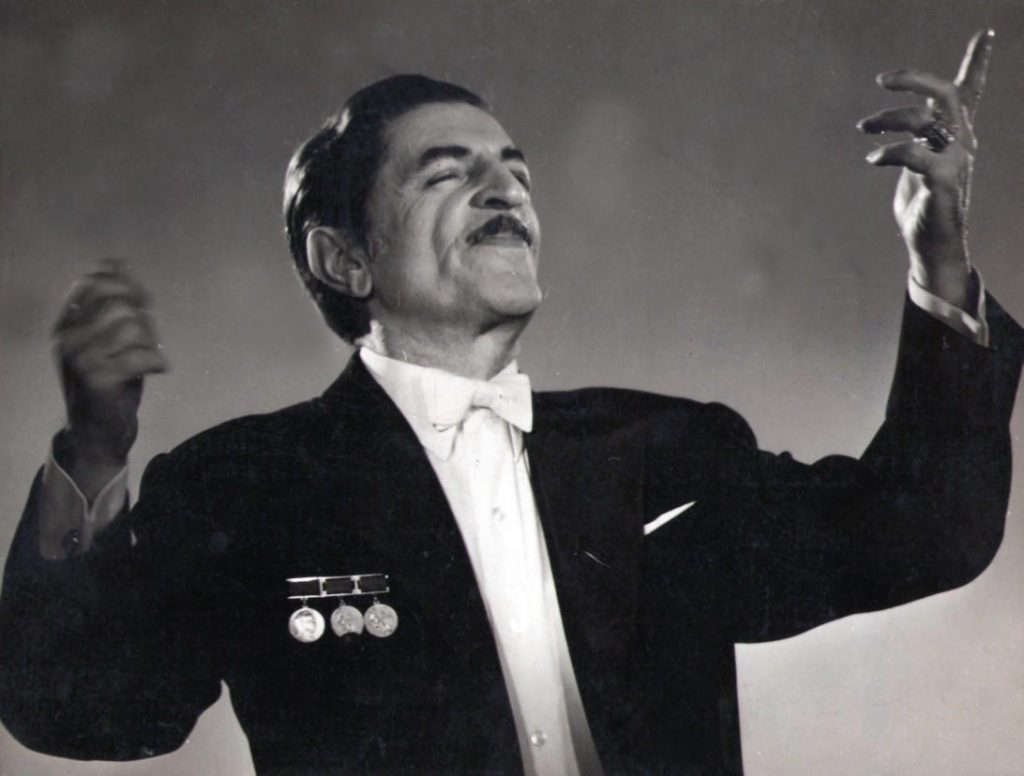

The history of modern musical art formation in Azerbaijan is associated with the eminent Shusha citizen Uzeyir Hajibeyov. It is no coincidence that Uzeyir Hajibeyov’s birthday, the 18th of September, is celebrated as the Day of Music in Azerbaijan, annually. One of the names closely associated with Uzeyir Hajibeyov is the name of the remarkable singer Bulbul. Uzeyir Hajibeyov has repeatedly admitted that while composing his opera Koroghlu (Blind Man’s Son), he primarily relied on Bulbul’s voice, talent, and skills. Bulbul performed the lead role in this immortal opera.

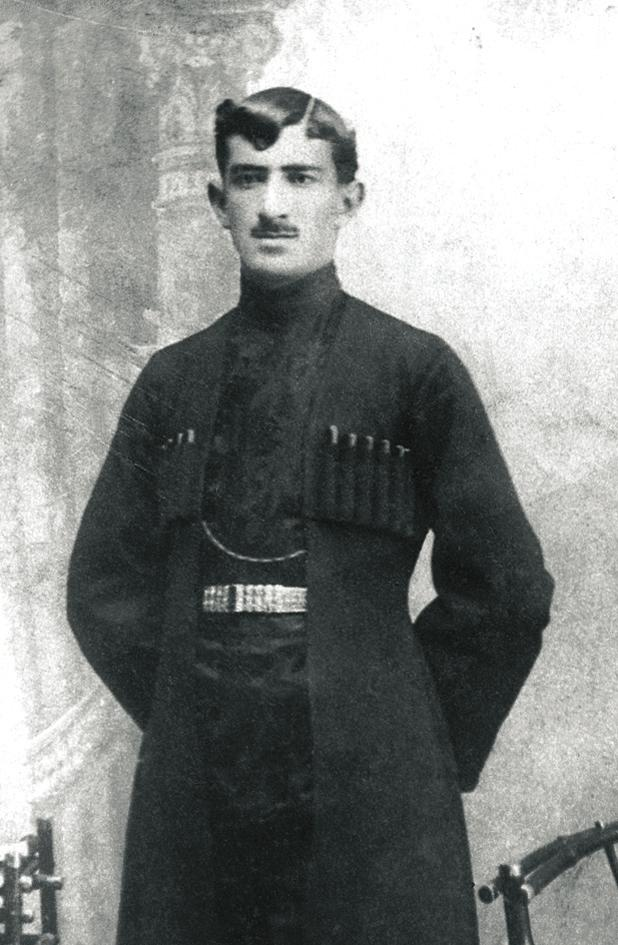

Bulbul (Murtuz Mammadov) was born in Shusha (1897-1961). He was fascinated by the beauty of his native land, its music, and the voices of famous singers he studied in his childhood. From the age of twelve, the young boy sang at weddings and other holidays in Karabakh. Soon, he became a renowned singer, receiving the pseudonym Bulbul, that is, “nightingale,” for his fantastic voice and brilliant imitation of nightingale trills. Until 1920, people mainly knew him as the mugham singer. After the revolution, he stood at the origins of the Azerbaijani Classical Vocal School, which adopted western traditions. Studies at the Baku Conservatory and the four-year-long internship in Italy with Belcanto masters helped Bulbul to become a renowned vocal master. As a result, in his singing, Bulbul skilfully combined national elements with Western singing techniques. Bulbul stressed the importance of folk music and instrument preservation and initiated publication of the School of Playing the Tar, School of Playing the Kamancha, and School of Playing the Balaban textbooks.

He founded the Folk Music Research Lab and initiated expeditions to Azerbaijan’s various regions to record folklore. Bulbul sang folk songs and tasnifs and appeared in leading roles in major operas of Verdi, Puccini, and Azerbaijani composers. On stage, he was always unforgettable. In 1961, two months before his death, Bulbul gave concerts in his native Karabagh. He sang in Shusha, where he spent his childhood and youth. The musician seemed to say goodbye to his land and paid his last tribute.

The famous Azerbaijani singer Rashid Behbudov of Karabagh began singing at the age of 18. He became widely popular after starring as Asker in the feature film based on Hajibeyov’s Arshin Mal Alan (The Cloth Peddler) musical comedy. The film became a triumphant success in more than 50 countries around the world. Hundreds of millions of people in all corners of the globe have seen and appreciated this witty musical comedy, its author, and artists. Rashid Behbudov was the first to create a Song Theatre, a theater for popular music in Baku. The group performed with concert programs in dozens of countries on five continents. Behbudov was an excellent performer of national songs. His repertoire included songs in the languages of countries he visited. (Isazade A. Musical culture of Azerbaijan. – Collection of articles “Karabagh.” Baku, 2004, p. 165).

One can talk endlessly about Azerbaijani musical culture figures born, lived, and worked in Shusha. It is the homeland for a galaxy of composers and instrumentalists, Afrasiyab Badalbeyli, Sultan Hajibeyov, Ashraf Abbasov, Suleiman Aleskerov, Gurban Primov, Ali Asger, Meshadi Zeynal, and the singer Mejid Behbudov, the father of the world-famous Rashid Behbudov. The master-symphonist, Fikret Amirov, son of a renowned singer, tar player, and composer Meshedi Jamil Amirov from Shusha. Fikret Amirov’s “symphonic mughams” are undoubtedly a new addition to the history of musical genres and forms. They are successfully performed in many concert halls around the world. The conductor and composer Niyazi is the son of the composer Zulfugar Hajibeyov of Shusha. During his lifetime, Niyazi frequently conducted unforgettable symphonic concerts held on an open-air at the Jidir Duzu. (an area located near Shusha, where historical horse races have been held since the Karabakh Khanate’s establishment).